How France viewed Scotland in the 19th century.

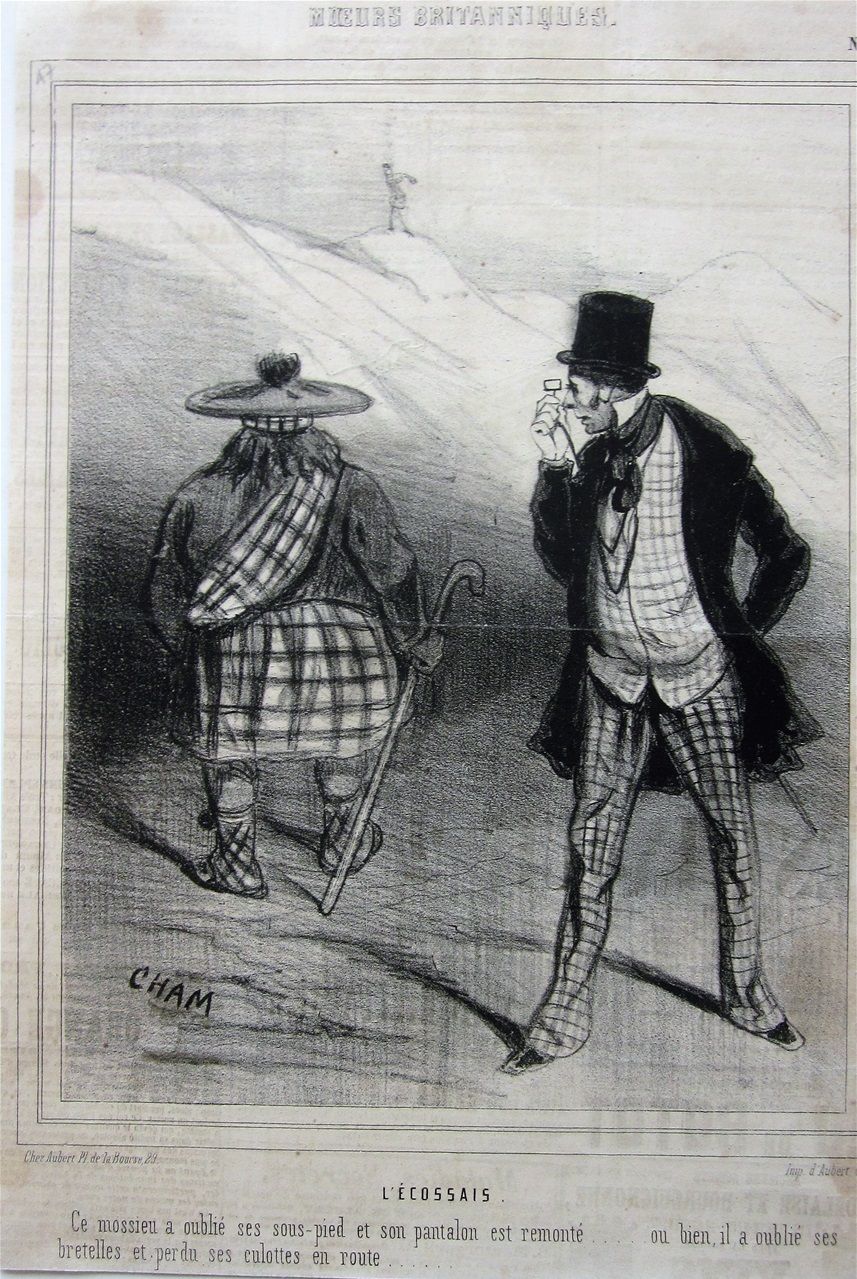

This man has forgotten his trouser strap and his trousers have gone back up...or he has forgotten his suspenders and lost his culottes on the way." A cartoon by Cham from the magazine Charivari.

[N.B. All translations are my own. Please excuse any errors, and feel free to suggest improvements!]

I do not pretend to be a historian who has studied in depth French and Scottish attitudes in the 19th century, but my superficial impression is that France viewd the Scots with a mixture of admiration and incredulity. Whilst they admired the bravery for which Highland soldiers were renowned, the French could never quite comprehend the kilt as a garment, and struggled to understand why it was worn, and what went on beneath it! Perhaps the combination of bravery within what they saw as effeminate clothing added to the confusion.

Le Petit Jupon Intrigant" - the intriguing little petticoat. An original watercolour by Rene de Pauw, c.1915.

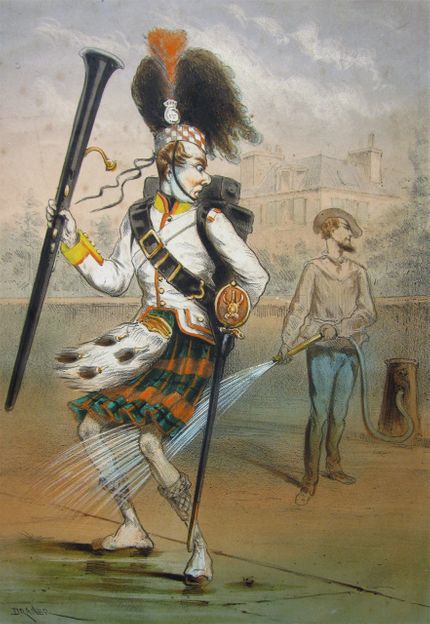

A print by Jules Renard. One of a series of 'Types Militaire.'

Even before the 19th century, comments were made by French visitors regarding Scottish dress. The two visitors whose journal is set out in Norman Scarfe's To The Highlands in 1786 (Boydell, 2001) noted that the kilt meant "the knees and part of the thighs are bare, which seems very indecent to us."

The geologist Faujas St Fond, travelling at approximately the same time, thought the outfit "is certainly the least adapted to a people who inhabit so cold and humid a climate."

Scottish Clan Chief, from M.A. Pichot's Voyage en Europe, 1825.

Here are some more early images of the Scottish dress:

Scottish Shepherdess, after Coupin, engraved by Vallon de Villenave, c1820

The popularity of Sir Walter Scott's poems and novels encouraged highly romanticised images of Scottish characters, none more so than this (left) engraving of a shepherdess, published in 1822, after an 18thC painting by Coupin. On the right is a Scottish milkmaid (source unknown).

Scottish Soldiers, by Carle Vernet, an engraving published by Bance in Paris, 1815, the year of the Battle of Waterloo.

But it was the Highland soldier who really captured the imagination. Both these images were published in 1815, the one on the right some 3 months after the Battle of Waterloo. The lady is dressed in a pattern based on tartan plaid, a style that became popular in spite of the defeat. It is hard to imagine German fashion taking off in this country shortly after the end of World War Two.

The New Fashion, or the Scots in Paris, an image after Noel Finart published 16th September, 1815 by Paul Basset.

"Scottish Plaid Dress in silk." From le Journal des Dames et le Petit Courrier des Dames a style worn in 1816.

"Modes Vraies. Travail en Famille." October, 1862. The children are dressed in full Scottish style.

The four fists give protection against Emperor Nicolas (of Russia). A cartoon by Cham, published in the Charivari in 1850, marking the build-up to the Crimean War.

These two images, published in the build-up to the Crimean War, demonstrate how by the mid-19th century, the distinctive garb of the Highlander had come to represent the entire British army.

Devil, Devil! I have presumed too much of my strength...I am beginning to comprehend that I am not able to go far with these two fellows on my arms. Cham cartoon, 1850.

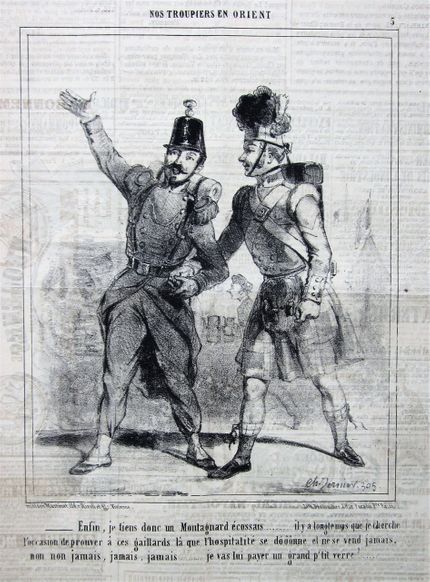

At last, I have a Highlander...I have for a long time been looking for an occasion to show that hospitality is given and not sold - no,no, nver, never, never...I am going to buy him a large drink.

Another cartoon in the series, this one by Charles Vernier, shows the two allies hand in hand. It was published in 1854, by which time the Crimean War was underway.

The spirit behind these next three cartoons is less clear.

All three are from the Charivari. Clearly, the return of the actor from London, dressed as a Scotsman implies ridicule, but what of the other two? Neither Scotsman looks much like a northern Casanova, and the Scots were not known for the excellence of their cuisine.

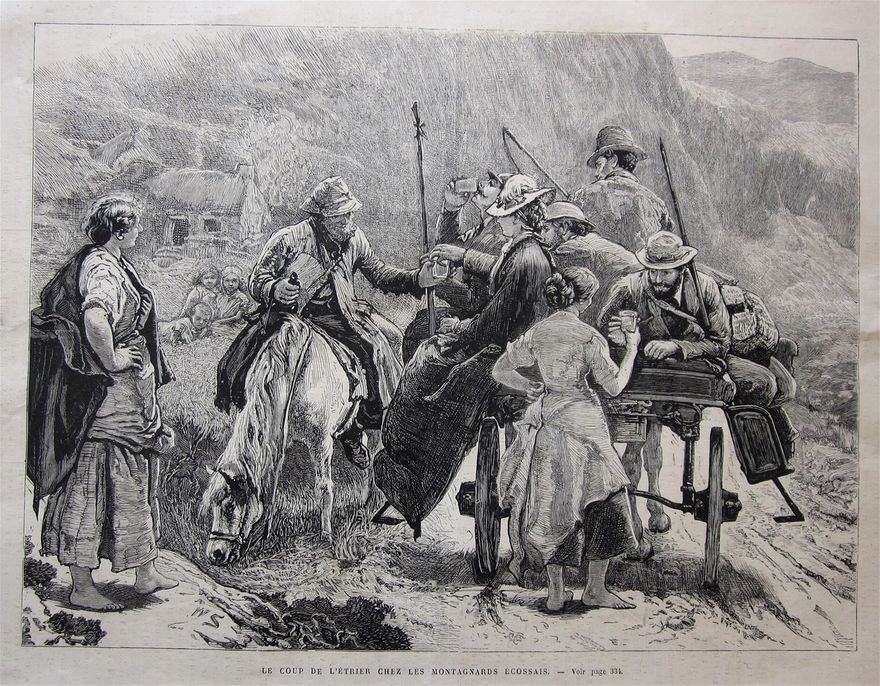

But their generosity was always acknowledged:

One for the road in the Highlander's home. From a French magazine (Charivari?), 1872.