Some Early Guide Books, and the Far North. Part One.

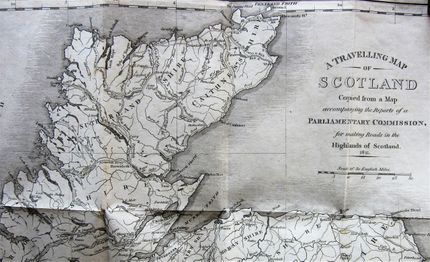

Detail from a Map of Scotland with the Roads, from Robert Heron's "Scotland Described..." 1799.

Had you decided to visit the far north of Scotland in the mid-18th century, you would have been unable to go to your local bookshop and buy a general guide to the region. By the end of the century, with the improvements in roads and increase in the number of people intent on travel, the demand for such guide books rose. Between 1800 - 1840, a number of general guides were published, culminating in the start of a mass of information for the intrepid traveller, in series of editions issued by publishers such as Adam and Charles Black.

I have a number of early guides to Scotland, and I think it is interesting to see what they make of the Far North. How many of the authors had actually been there?

The Earliest Guides.

Accounts of the north-west of Scotland had been available in the 17th century. Sir Robert Gordon's Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland, first published in 1813, but written in 1630, gives a good description of the county at that time, and Richard Francks' Northern Memoirs, again published later (1821) but written in 1658 claims to cover much of the north. It is an altogether more obscure text, much of it a discussion concerning angling, between two characters: Theophilus and Arnoldus. Although Francks hints that he has covered the entire nation, it appears that he actually visited only the accessible parts of Ross-shire and Sutherland, on the east coast. His reports of the interior in those regions are simply hearsay and rumour. Anyway, accounts such as these were not guides as such, to be put in the pocket of the visitor, and that applies as well to the impotant narratives of the 18th century, such as those of Bishop Pococke (1760), Thomas Pennant (1769 & 1772) and Charles Cordiner (1776). However, before the century was out, publishers began to issue what might be called general guides to the country, designed for the interested visitor.

In 1799 T. Brown published a 'New and Enlarged Edition' of Robert Heron's Scotland Described, a topographical description of all the counties of Scotland. The map at the top of this article is taken from this edition, and shows the roads of the northern part of the country, as he believed existed. Each county is given its own chapter, the one on Lanarkshire, for example running to 15 pages. Sutherland receives less attention, with barely five pages of description. Reading this chapter, it is clear that Heron had not visited these parts in person: his map shows roads, such as that along the north coast, that did not exist, and his account describes vaguely a road that "runs along the banks of Loch-Shinn, and proceeding forward, goes round the whole county visiting many villages of small importance....Nor does this road cease its circumambient wanderings until it hath traversed the whole of the north coast with many windings, and at last entering the county of Caithness at Kirktown." Any traveller with this guide in his pocket would have been at least disappointed, and probably alarmed to find that very little of this supposed road existed. As late as 1820, Duncan's Itinerary was stating the need for a guide along the north coast. Perhaps acknowledging that his research was not fully reliable, Heron does admit in the preface "...some inaccuracies may have dropped from the pen...The candid reader, however, will easily recollect that imperfections of this nature are more or less incident to all productions of this nature." Not much comfort to the visitor, lost, looking for a road in the wilds of Sutherland!

Another, much more reliable guide that was published in the same year, 1799, was the Hon. Mrs Murray's of Kensington A Companion and Useful Guide to the Beauties of Scotland.

This guide is in part an account of the journey Mrs Murray made, but she is at pains to point out "... to the traveller what is worth noticing in his tour, with the distances from place to place; [it] mentions the Inns on the road, whether good or bad; also what state the roads are in; and informs him of those fit for a carriage, and those where it cannot go with safety. In these respects the present Work differs from any other publication of the kind." Certainly a useful book for the pocket of the visitor to Scotland, but of course Mrs Murray could go no further north than Inverness, there being no roads at all into Ross-shire and Sutherland at that time (apart from that up the east coast), and certainly nothing suitable for a carriage.

However, as she points out, her account did offer new and specific advice to anyone travelling the same route as she had followed when she set off "with my maid by my side, [and] my man on the seat behind the carriage" on May 28th, 1796. In the introduction, she had strongly urged the traveller to add a seat at the back for their 'man',as "if he is not on a horse it will save you money and mean he is always at hand, [otherwise] he is hardly ever with you...for opening gates, or in case of accidents." Indeed, she cites one example when he spotted that one of her shackles had borken. He "instantly called the postillion. Had the carriage not stopped immediately, I do not know what might have happened."

She lists all the spares you might need in case of such accidents and breakdowns - linch-pins, four shackles, a turn screw, hammer, straps, etc. - and recommends fitting a box, hinged to the side of the carriage so that it "should fall down by the hinges, at the height of their [the passengers'] knees, to form a table on their laps; and part of the box below the hinges should be divided into holes for wine bottles, to stand upright in. The part above the bottles, to hold tea, sugar, bread and meat; a tumbler glass, knife and fork, and salt-cellar, with two or three napkins." Taking no chances, she adds "the box to have a very good lock", and also suggests taking "bed-linen, and half-a-dozen towels at least, a blanket, thin quilt, and two pillows." Her faith in Scottish inns and hospitality is obvious!

Once on the tour, she offers advice on how to reach places, what to wear - spare clothes at the Fall of Foyers, where "the spray of the Fall itself...[will] make you wet through in five minutes", and warm clothes for Corryairraick, where at the top it will be cold. The descent from this summit she suggests should be done on foot, it being both steep and a constant zig-zag. The road from the Crook of Devon to Dollar is "as bad a road as ever carriage passed", while at the ford that crosses the river at Glen Finglass, the traveller should "take care...I advise you to walk over the foot bridge of wood and turf, and let the carriage go empty through the river." At the foot of Loch Catherine [Katrine], "you must quit the carriage, [and] take care your horses do not get bogged, as mine did, whilst the driver was staring at the wonders of the Trossachs."

Few other guide books offered such specific advice, and certainly no other book at that time offered more details on travelling in the Highlands. but Mrs Murray did not venture into the far north-west. Some six years later, George Aleaxander Cooke published a small work devoted to A Topographical Description of the Northern Division of Scotland... Each county, Inverness, Cromarty, Ross, Sutherland and Caithness was given its own chapter, sub-divided into a description of each parish.

Much of the information had come from earlier accounts (Pennant, etc.), whilst population figures were derived from the First Statistical Account of Scotland, which had been published in 1799. Cooke provides interesting little snippets, such as details of Ben Wyvis (Benuarish here) which "is constantly covered in snow; and the tenure of the part of the estate of the barons of Foulis was by the payment of a snowball to his Majesty on any day of the year required." But Cooke's small account offers little in the way of details of roads, and how to get around the region, instead simply dismissing the north-west part of Ross-shire as "desolate and dreary; nothing is here seen as far as the eye can reach but vast piles of rocky mountains, with summits broken, serrated and aspiring into every form, some of which are always covered with snow."

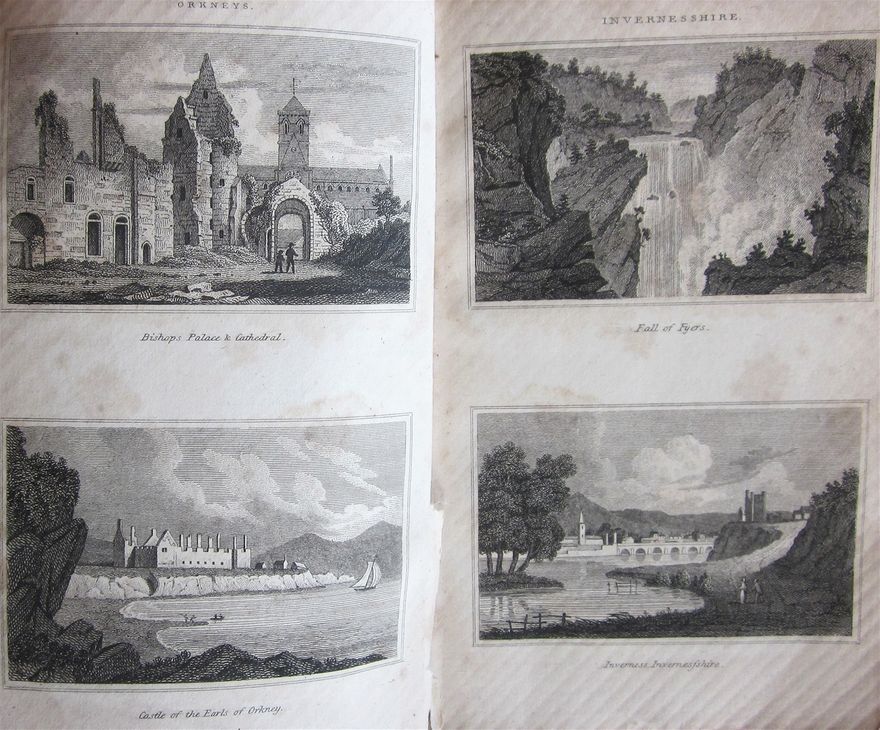

The four small vignettes found in Cooke's Description of the Northern Division, two of them Orkney scenes, and the others Inverness, and the Fall of Foyers.

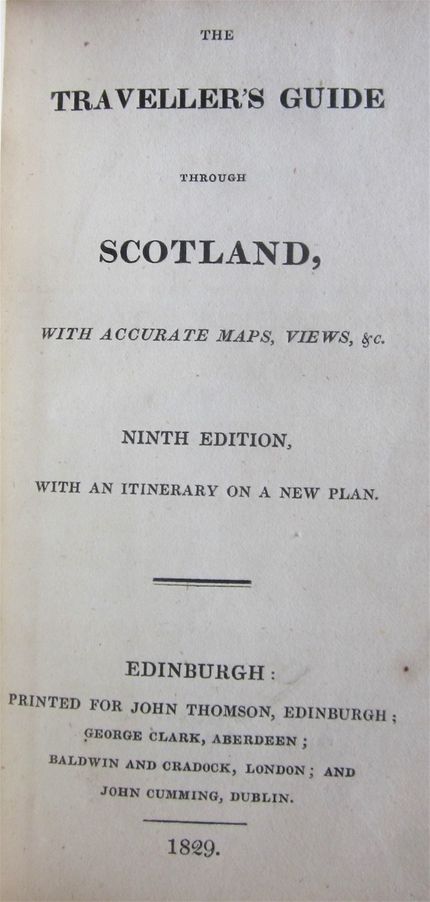

The same criticism cannot be levelled at The Traveller's Guide Through Scotland and Its Islands, which was issued in a number of editions, the third being issued in 1806.

I have two editions of this work, the earlier published in 1811 (a fifth edition). The traveller to the far north would have been again a little disappointed with the map supplied in this edition, for none of the work on the roads in this region had yet begun. The map is based on that provided by the Parliamentary Commission in 1805.

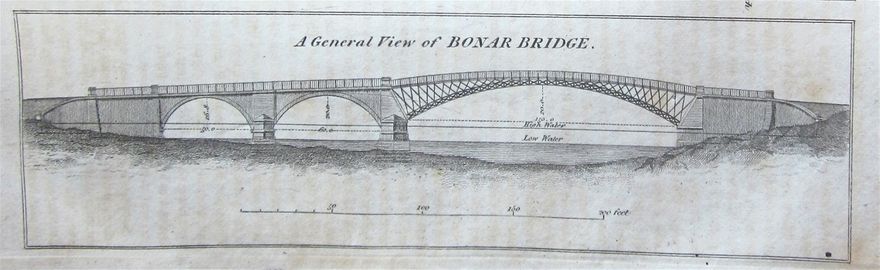

Moreover, in a large guide numbering over 500 pages, with impressive details of counties further south, this edition manages only seven pages on Sutherlandshire. Still, this is a proper up-to-date guide for the traveller, and it is honest about the tracks that exist inland: they "are difficult to the people of the country, on their own horses, though accustomed to the bogs. To Strangers and to other horses, these paths are always dangerous and sometimes impassable." It notes that work on the road from Criech to Tongue has not yet begun, and that a bridge over the Kyle of Sutherland is to be built, called Bonar Bridge. This was to be of enormous importance, linking Sutherland with the regions further south and removing the need to use the dangerous Meikle Ferry.

So far as Ross-shire is concerned, a detailed account of the road north from Inverness on the east coast is given, and mention is made of roads "begun, or projected in this county, which, when completed, will considerably improve its internal communications.

The other edition of this work that I possess is the ninth edition, dated 1829. By this time the situation in both Ross-shire and Sutherland had changed considerably: the bridge at Bonar bridge was in place, and a road north through the centre of the region, terminating at Tongue had been completed. There was also a road linking Bonar Bridge with Scourie on the west coast, though, to the Road Commission's deep regret, they had failed to complete the link down to Ullapool.

The 1829 edition of Thomson's Guide contained this scarce image of Bonar Bridge. The bridge was thought a great wonder at the time, one local likening it to "a spider's web in the air." It survived until 1892. The bridge that now crosses the Kyle of Sutherland is the third to have been constructed there.

This 1829 edition adds little to the description of travel within Ross-shire, but there is an interesting addition to the section on Caithness-shire, "...an account of Lord Reay's Country, written by a gentleman , in a letter to his friend...in November 1827." I have been unable to discover who this gentleman was, but his account is certainly of interest. He writes of their "intention of striking into the interior of the country" and so they leave Dornoch on Garrons, the small highland ponies suited to the terrain, and headed for a "snug little inn" at Lairg, where they spent the night.

Next morning saw them "on our saddles, merrily prancing it along the margin of the loch [Shin]" - an unusually upbeat description of progress on a highland pony! They then proceeded up Telford's new road to Tongue, which interestingly the writer describes as "more a well-kept garden walk than His Majesty's highway, its only fault being its extreme narrowness". But once heading westwards from Tongue towards Eriboll, "a guide became necessary - our route lying either across the rugged mountain, or over the trackless waste of the Moin, in many parts of which the ground is so boggy that our horses frequently sunk beyond their knees." This must be one of the last descriptions of travelling over the dreaded Moin before the Duke of Sutherland's road was constructed in 1830.

The view that greets you as you come over the hill from Loch Hope, with Loch Eriboll stretching before you. Ard Neakie is the isthmus in the foreground.

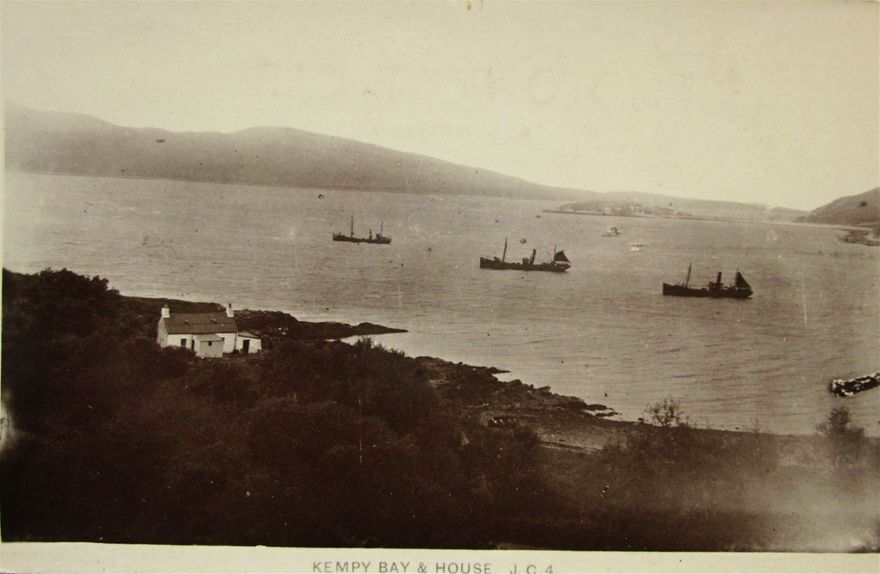

The party marvels at the view of Eriboll, presumably seen from above Ard Neakie. "A fleet of thirty sail, all wind-bound, rode at anchor on its smooth waters; and their different yawls [a two-masted sailing boat] were seen gliding swiftly along in every direction, whilst numerous parties of sailors were enjoying their rough sports on the beach."

Kempy Bay & House, a scarce postcard of fishing boats on Eriboll, looking north towards Ard Neakie.

Unfortunately, it wasn't just their sports that were rough, but also the sailors ("many of whom appeared to be foreigners") themselves, and the party found itself followed by a group which the writer describes as "a more ruffian-looking set of fellows I never beheld." To make matters worse, the travellers' guide left them when they were two miles from Eriboll, assuring them that the route was clear. "We had not, however, gone on but a short distance, when the perplexing number of paths that crossed one another in every direction, and the growing darkness of the night, made us heartily repent having ventured unguided at such an hour through such a country." They proceeded warily, their pursuers gradually closing the gap behind them, when just as they reached "the brink of a very steep eminence", a party of gentlemen appeared which persuaded the ruffians to disperse, and the party was guided to "the kind hospitality of the family at Eriboll" (I suspect this was the Clarke family, who entertained Murchison and Nicol on their geological expedition in 1855. Another branch of family had entertained William Daniell at Glendhu). In all the accounts I have read of travel in the far north, this is one of the few (possibly the only account) where there had been any sort of threat.

Next day, the party proceeded on to Rispond, at the head of the loch passing under "the stupendous rock of Craigenefielin, whose frowning front, as it seems to overhang the road, fills the astonished beholder with awe." This is Creag na Faoilinn, an important site for geologists that Murchison failed to study when the Highlands Controversy was in full debate.

Interestingly, much of the description of Loch Eriboll in this account matches closely that found in the Andersons' later guide published in 1834 (see Early Guide Books, Part 2). Whether this account is actually by one of the Andersons I do not know. Perhaps someone can enlighten me (greywings89@gmail.com)?

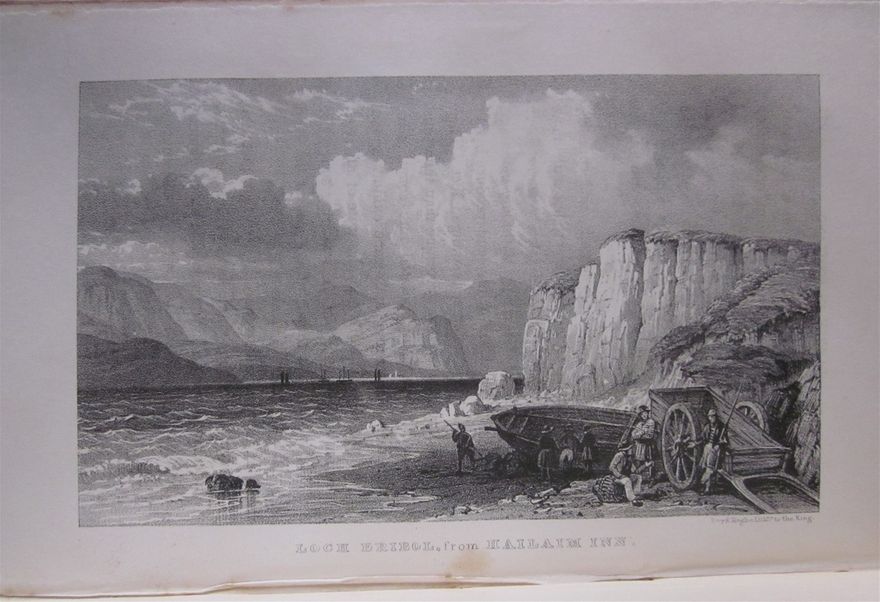

An early engraving looking south from Ard Neakie on Loch Eriboll, the rock of Creag na Faoilinn seen in the middle distance. From Charles Lessingham Smith's "Excursions Through the Highlands..." 1837.

Soon after Creag na Faoilinn, they came to "the termination of the metalled road - the remainder being only in the course of formation; leaving us under the necessity of again tempting the perils of bogs and pitfalls." However, they progressed without too much difficulty, pausing at Smoo Cave, the appearance of which is "so very extraordinary, that a stranger feels surprised never to have read or heard of it before." Evidence again of just how unexplored this region was.

They could procede no further than Durness "owing to the extreme badness, or rather total want of roads to the westward." A point to be noted by those cartographers who enthusiastically showed roads all the way round the north-west! They retraced their steps, and returned via Strathmore, passing Dun Dornadilla beneath Ben Hope. "Before reaching Aultnaharrow, we had again to encounter the danger and difficulties of a pathless way, - in the course of which we had frequent cause to bless our stars that our ponies exhibited many unequivocal proofs of possessing, in no slight degree, the valuable bump of cautiousness."

All in all, this is an excellent account of the difficulties facing travellers in the far north at a time when road infrastructure was improving so dramatically further south.